|

|

|

|

You are in: Future Challenges : Peak Oil

(The Return of) Peak Oil

All industrialized societies are based on oil. It is, in fact, quite difficult to overstate just how dependent on oil human civilization has become. Oil is not only the lifeblood of most means of travel, but is also relied upon to make pesticides and to harvest and transport most of our food. Indeed, in many developed nations, every calorie we eat consumes about ten calories of oil. Many products are also manufactured in whole or part from oil, including plastic product casings, plastic bags and containers, nylon clothing, many medicines, and the tarmac on our roads. We should therefore be paying far more attention to the inevitable reality that our first planet provides us with a finite supply of oil that cannot last forever. Ten and even five years ago, concern was rising about the pending situation of "Peak Oil". This refers to the point in time when global oil production reaches its inevitable maximum, and beyond which global oil production will start to decline. Today there is little popular concern about Peak Oil, and indeed those of us who still highlight this future challenge are viewed as scaremongers and cranks. The reason for this mainstream change of emphasis is also two-fold. Firstly, in the past few years many nations have begun to exploit reserves of unconventional oil (such as oil fracked from shale or extracted from tar sands), with the United States having ratcheted unconventional oil production to such a level that it has overtaken Saudi Arabia to become the world's largest oil producer. Secondly, and in part related to the increasing exploitation of unconventional oil, the price of oil has dropped from well over $100 a barrel between 2011 and 2014, to under $30 a barrel in January 2016. This price fall is clearly attributable to a glut of oil supply in the market, with the BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2015 reporting global oil production growth in 2014 to be more than double that of the growth of global oil consumption. Over-supply is also expected to get worse with the re-entry of Iran into the global oil marketplace in 2016. So, against this backdrop, how can Peak Oil still be a future concern? Well, the first thing to appreciate is that the ongoing discovery and exploitation of new oil reserves is entirely consistent with the theory of Peak Oil. Although fossil fuel oil is a finite resource, there are almost certainly some (if fewer) reserves left to be discovered, as well as many already known conventional and unconventional reserves that will become economic to exploit as technologies improve, prices rise, governments permit, and needs dictate. We are therefore likely to go on discovering and exploiting new oil reserves -- both conventional and unconventional -- for a great many decades. Even so, if our discovery and exploitation of new reserves does not match the depletion of existing fields, then at some point global oil production will hit a maximum and subsequently decline and we will reach and then pass Peak Oil. We may, in fact, already be experiencing the maximum ever level of global oil production -- or in other words Peak Oil -- about now, with OPEC and other conventional oil producers still extracting large quantities of oil, and new unconventional oil producers like the United States bolstering production further still. Given that current oil production levels exceed global demand -- so driving prices downwards in the short-term -- if we are at Peak Oil about now it really does not matter (well, at least not in short-term economic terms). However, beyond the peak, global oil production can only fall, and as and when this occurs we will inevitably reach a point where combined conventional and unconventional oil production will fail to meet global demand. In this content, it is well worth noting that at least 75 per cent of conventional oil fields (such as those in the Middle East) are thought to have flat or declining production (although getting good data on oil production, particularly in the Middle East, is very difficult indeed). It also needs to be understood that while large, conventional oil fields (and once again those in the Middle East) take decades to fully exploit, most unconventional oil deposits are fracked or otherwise tapped to exhaustion in not that many years. Indeed, as Bloomberg Business cautioned in 2013, "shale wells start strong and fade fast". This means that the oil renaissance in the United States may be relatively short-lived, and will require exponentially increasing efforts in an attempt to maintain its current level of output. Or as the International Energy Authority (IEA)'s report World Energy Outlook 2015 very recently expressed the situation, the rise of unconventional or "tight" oil is "ultimately constrained by the rising costs of production, as operators deplete the 'sweet spots' and move to less productive acreage". The IEA went on to predict that the output of US tight oil will reach "a plateau in the early-2020s", before "starting a gradual decline".

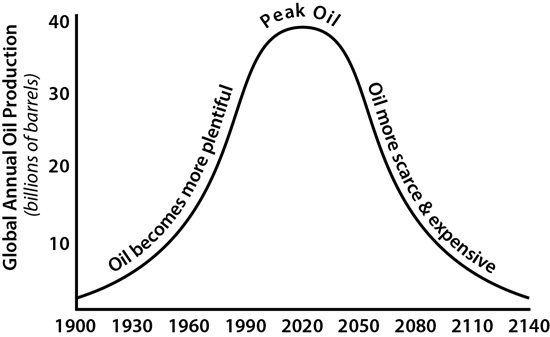

The Peak Oil CurveRight, with an appraisal of the current and unusual short-term situation out of the way, let us turn out attention to the longer-term practicalities of oil supply. For more than half a century it has been known that the rise and fall of oil production in a particular region follows a so-termed "bell curve". The first such curve was drawn in 1956 by geophysicist Marion King Hubbert to predict when (conventional) oil production would peak in the United States. Hubbert estimated this would be between 1966 and 1972. Most people at the time dismissed Hubbert's meticulous work as ridiculous. Nevertheless he was right, with the actual peak occurring in 1970. The diagram below charts a possible bell curve for global oil production as things may currently stand. The historical data on the left-hand side of the curve has been significantly approximated for clarity. The exact dates on the horizontal axis are also a matter of debate. This said, the diagram is I think reasonably indicative of the probable supply of fossil-fuel oil (both conventional and unconventional) in the decades ahead.  Peak Oil ImplicationsAfter Peak Oil becomes a reality we will start to experience a gradual fall-off in production. Quite how significant this may be will depend on the demand for oil at that time, which in turn probably depends on two key factors. The first of these is economic growth -- particularly in newly industrialized countries (NICs) like China, India and Brazil. Today, China's period of spectacular economic growth appears to be coming to an end, which in turn will lessen the potential global demand for oil, and will allow humanity to live within a smaller oil supply envelope without incident for a longer period. The second key factor that will determine the significance of oil production reaching its peak is the global response to climate change, and where once again what will happen in newly industrializing nations, and in particular China, will prove critical. Already China leads the world in developing and implementing alternative energy technologies, including wind farms and solar power stations. If China continues to accelerate its uptake of such technologies -- both in an attempt to improve energy security and to try and limit climate change -- then the relative impact of Peak Oil will be reduced. Even so, at some point in the next two decades I think it is very reasonable to predict that a gap between oil supply and oil demand is going to open up that will have stark economic, political and practical implications unless we have developed sufficient energy and material-supply solutions that do not depend on the extraction of fossil fuel reserves. Or to put things another way, I would predict that Peak Oil will become a serious global challenge sometime between 2025 and 2035, with the date being closer to 2025 if the global economy picks up and/or we continue to pay scant attention to the future challenge of climate change.

Another Failure of EconomicsThe security of our civilization's energy supply, and particular the future provision of fossil-fuel-based oil, are matters of very great significance but also heated and deeply eco-political debate. Ten years ago there was a great deal of interest and reporting in this area. Yet sadly, the short-term glut in supply caused by the rapid development of unconventional oil production, coupled with the associated and rapid fall in the price of oil, has very much stifled discussion. And yet, the common sense reality -- that our first planet has a finite fossil fuel supply that we are using up rather quickly -- has not altered one jot. Most industry forecasts are now rather bullish, indicating that there is nothing to worry about when it comes to oil supply. But look at the data behind the spin, and it is still very clear that we should have concerns for the longer-term. For example, to cite a figure from the 2015 edition of the highly respected annual BP Statistical Review of World Energy, the current best prediction from this very large industry player is that, at the end of 2014, the world had about 1,700 billion barrels of proven and recoverable oil reserves remaining -- a supply that would last about 52.5 years at current consumption levels. Basic mathematics tells us that this means we have a proven oil supply until about 2066, and that in turn Peak Oil will become a very significant challenge many decades before that. Granted, we will continue to discover oil reserves that are currently unknown (and which are hence not included within the aforementioned figure). Indeed, even the Hubbert Curve above assumes oil production well beyond 2066 on this very basis. But as I hope to have made clear, the issue surrounding Peak Oil is whether we will continue to discover new oil reserves faster than we will deplete existing ones, and the evidence suggests that we will not. For many years a great website called The Oil Drum provided great information on Peak Oil. Sadly, in 2013, the site closed -- although it remains live as an archive resource. One of its last posts -- a very detailed article on World Oil and Gas Production Forecasts Up to 2100 by Jean-Marie Bourdaire -- makes very interesting reading, and notes the difficulty of preparing good forecasts in the absence of good data from an industry and many nations with strong, short-term vested interests. The post also predicts "that world oil (all liquids) production will peak before 2020, Non-OPEC quite soon and OPEC around 2020". It also goes on to suggest that "OPEC will cease to export crude oil before 2050" and that "the dream of the US becoming independent [in the long-term] seems to be based on resources, but not on reserves". Ultimately, the real problem we face is an industry, a global economy and a civilization obsessed with short-term economic decision making. Right now, it is difficult to credibly raise the spectre of Peak Oil when there is an over supply, the price per barrel is under a third of what it was a few years ago, and the world's economists agree that this situation will continue for the foreseeable future (which in economic and political terms means only a year or few from now). The alarming implication is that, even with the common-sense inevitability of Peak Oil on the horizon, we are in danger of consuming more of this finite resource than is prudent, and in the process emitting more and more greenhouse gas emissions. A better example of the need for the death of economics as our primary decision making mechanism really is difficult to highlight. Finally, it is also worth noting here that even if the exploitation of unconventional oil reserves may extend the deadline for Peak Oil out by five years or even decade, it will not assist with the longer-term provision of energy in a sustainably economic fashion. This is because of the relatively high cost, or energy return on investment (EROI), of unconventional oil extraction versus that for conventional petroleum -- an issue I address in the following video: More information on Peak Oil can be found in my book 25 Things You Need to Know About the Future. The actions that we need to be taking in preparation for Peak Oil are also covered in depth in its sequel Seven Ways to Fix the World. Return to Future Challenges. |

Even in the face of a short-term glut in supply and an accompanying price fall, we are still approaching that point in time when there will be a growing shortfall between oil demand and oil supply.  Learn about Peak Oil solutions |

|

|